Within minutes of turning on to 85N, and only an hour shy of Scottsdale, I see my first saguaros,  white flowers peaking their green and fleshy scales; and I see two hell-bent roadrunners pound the dirt with near-invisible legs. I also watch as a jostling hay-truck explodes a tumbleweed with its grill.

white flowers peaking their green and fleshy scales; and I see two hell-bent roadrunners pound the dirt with near-invisible legs. I also watch as a jostling hay-truck explodes a tumbleweed with its grill.

Apparently I’m in Arizona.

I was actually welcomed to AZ a number of miles back courtesy of a buckshot greeting sign just outside of Yuma, this right before the Border Patrol agents with their nausea-green cars and loose-leashed dogs quickly unwelcomed me at the checkpoint.

The left-hand turn out of Gila Bend, north toward the 10 junction, provides better welcome. That’s when the landscape takes on a more Arizonan trope, the kind of landscape you’d find properly and agreeably silhouetted on a license plate; the stuff of gas-station postcards. There’s iconic cacti, the craggy and nearer horizons. Yellow-banded Gila Monsters, you imagine, looking to hitch rides in convertible jalopies through the blown-out countryside.

The 8W-85N convergence is where you leave the desert floor and its blankness. It’s where, too, you retreat from the Yuma silo painted with ‘0 sea level’ markers (and where, too—despite claims to the contrary—the elevation is actually fifty-two feet). By turning left and north, you veer toward the saguaros and the Pre-Cambrian rocks that rim the deserts.

(and where, too—despite claims to the contrary—the elevation is actually fifty-two feet). By turning left and north, you veer toward the saguaros and the Pre-Cambrian rocks that rim the deserts.

Camelback Mountain couching Scottsdale is made of the same ragged basalt that outskirts Imperial County. It’s of similar geography to the compressed-fault tombstones signaling Vegas; similar, even, to Antarctica, which though covered in ice, bares the same jagged geographical teeth—in bluish regale, but still remarkably parallel in desolation.

It’s lonely out here. The roadrunners must either be running away or toward something.

The mirrored patches ahead of me on the horizon look like some form of black ice, but it’s a trick of the heat. Arizona’s hot, especially for April. The dashboard thermometer flirts with three digits and I should’ve gotten my vehicle tuned prior to leaving San Diego. The idea of breaking down in the desert is a formidable worry especially with the white road fading into white horizon. It’s a long drive and only sometimes does the chaparral turn a different shade of brown. There is a sense of endlessness.

‘Welcome to Arizona.’ This is certainly not my favored state and, I’m arriving in an equally and altogether unfavorable mode, anxious and alone in the car. I’m just trying to make it to Phoenix on time, goddamn the desert in between.

***

My final destination is the Iris Award ceremony—the Oscar gala of bloggers—and though I’ve nominations I’m really proud of in my back pocket, there’s the insufferable Mojave to cross.

In Greek mythology, Iris is the errand-running messenger of the gods and a minor deity. She’s Hera’s handmaiden, classically symbolized by the rainbow.  If you make a slip of the tongue, though, say ‘Isis’ instead of ‘Iris’—well—that’s an Egyptian goddess. Her mother’s name is Nut.

If you make a slip of the tongue, though, say ‘Isis’ instead of ‘Iris’—well—that’s an Egyptian goddess. Her mother’s name is Nut.

Nut, nutters.

Iris is the daughter of the sky and the sea as mythology goes. This makes the rainbow appropriate symbol if you choose to consider rainbows, which I don’t this deep into an unpleasant drive. Currently everything is white and colorless; rainbows or oceans out here in the desert should be something out of the question. There is, however, the strange fact of the Salton Sea, the one that’s presently drying and dying, precipitating its own salts south of the 10.

(Take Exit 131. It’s about fifty miles north of the dunes).

The Salton Sea pre-dates Palm Springs as a destination. Both have been advertised as paradisiacal oases in the desert. Why we need parentheses of desolation to isolate and qualify paradise, I don’t know. Maybe paradise is made so only by fact of contrast.

Could also be that you can get Eden-rivaling dates in both Palm Springs and the Salton borderlands, fruits worthy of the first Garden.

Either way, to get away from it all you have to literally get away from it all, in which case there are desert islands, or—as proxy—actual deserts. Water’s only a factor sometimes. Remember that Antarctica is a desert, which, if melted, could quench a considerable thirst. Melting the Mojave wouldn’t result in as much: you’d be left with a great and unnavigable sheet of glass, sand in your mouth and grit in your teeth. Still, paradise exists out here in the parch, unbelievable as it sounds.

Used to be that thousands of birds—four hundred varieties—visited the Salton Sea during the annual Pacific migration: pelicans and arctic geese, terns and stilt-legged cranes. There were also the Hollywood birds with their as-conspicuous gams, their feather boas, and millimenary plumage. They’d arrive with lecherous and Bryll-creemed escorts at their wing, gleaming hair-do’s fast flattening in the sun. Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, Sonny Bono, the Marx Brothers.

Used to be that thousands of birds—four hundred varieties—visited the Salton Sea during the annual Pacific migration: pelicans and arctic geese, terns and stilt-legged cranes. There were also the Hollywood birds with their as-conspicuous gams, their feather boas, and millimenary plumage. They’d arrive with lecherous and Bryll-creemed escorts at their wing, gleaming hair-do’s fast flattening in the sun. Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, Sonny Bono, the Marx Brothers.

Rock Hudson did a photo-shoot waterskiing the Sea with George Nader. They never co-starred together onscreen, just on Salton waters. Hudson, instead, did a turn with James Dean on the set of ‘Giant’. Dean died soon thereafter in a car crash 28 miles east of Paso Robles, a place near as desolate as its Salton cousin far off to the south.

The fields near Paso Robles and south of Fresno are harrowed and fallow, much like the Imperial Valley outskirts that, similarly, haven’t received much of the Colorado River’s water over the years. The Salton Sea is actually an accident of the Colorado, the River’s aqueducts having overflowed to create the fantastic puddle way back in 1905. Astoundingly the Sea rests just 200 feet above Death Valley’s greatest depths and currently receives only a slight fill from the polluted waters of the American River. Through nature’s mechanics, the Sea’s artificiality has slowly become apparent, precipitated salts and algae blooms winnowing fish stocks over time into just junk proteins: catfish, carp, and tilapia that now garbage the turgid waters.

Man—the Salton Sea used to be so happening. Now it’s nearly dead.

Patio umbrellas are long folded, and meanwhile the bioaccumulation of selenium in the Sea’s fish stock has left a shoreline of limpid birds with botulism. Poor birds. The sun is a constant and evaporative thing.

I drive over New Wash just past the dunes, and there’s a change in the guard railing, a change, too, in the color of the road: the asphalt turns from black to white. The New Wash is just cracked earth and chaparral when I blow by at an 85 mph clip.

When James Dean died, it was because his Porsche violently slammed into a roadside guard railing, also at 85 mph. Alec Guinness—future and sage Obi-Wan—warned James that he’d certainly die in his ‘sinister’ vehicle a week before Jimmy actually did. Dean crashed avoiding an oncoming Ford Tudor, while purportedly muttering: ‘That guy’s gotta stop. He’ll see us.” Famous last words, and tidy fulfillment of Obi-Wan’s prophesy. Dean’s chassis was found face down in a gully, James’ neck broken twice over. He was declared dead before the ambulance could make it to Paso Robles.

When James Dean died, it was because his Porsche violently slammed into a roadside guard railing, also at 85 mph. Alec Guinness—future and sage Obi-Wan—warned James that he’d certainly die in his ‘sinister’ vehicle a week before Jimmy actually did. Dean crashed avoiding an oncoming Ford Tudor, while purportedly muttering: ‘That guy’s gotta stop. He’ll see us.” Famous last words, and tidy fulfillment of Obi-Wan’s prophesy. Dean’s chassis was found face down in a gully, James’ neck broken twice over. He was declared dead before the ambulance could make it to Paso Robles.

Coincidentally, they sell date shakes on Route 466 just past the marker where Donald Turnupseed’s Ford Tudor nearly met James Dean’s Spyder. There’s a fifteen-foot cardboard poster—Jimmy in his red leather jacket—featured at a gas station just half-mile shy of the crash site. It’s that spooky Salton Sea vibe all over again: the ghosts of Hollywood past, the fact of Eden-worthy dates in the oases.

I think these things at 85 mph when leaving Salton in the rearview, the peril of the road and its left-behind ghosts, James Dean and his broken body, his internal injuries. I think: we all suffer from internal injuries; it’s just that James Dean died from them.

Turnupseed, meanwhile, survived the crash. His Ford Tudor just wound up facing the wrong way in the westbound lane. How about that—the road spares itself some lucky trespassers. You should see where all this happened, where James met his fate that night and where Turnupseed walked away unscathed. It’s a really really forgettable place.

Turnupseed, meanwhile, survived the crash. His Ford Tudor just wound up facing the wrong way in the westbound lane. How about that—the road spares itself some lucky trespassers. You should see where all this happened, where James met his fate that night and where Turnupseed walked away unscathed. It’s a really really forgettable place.

***

There’s a change of guard-railing when passing over New Wash, and the sudden appearance of thin grasses. There’s supposed to be overflow from the Salton Sink here too, but the tributary veins that bleed the Salton Sea are dried up. Chamise blooms in the arroyos, which means it’s existed in the wash for at least seven years without having once been drowned.  Chamise, after all, takes seven calendar cycles to mature before it becomes dusty, musty, and white-flowered—seven years to muster just one blossom; meanwhile, the chamise I drive past is on full display.

Chamise, after all, takes seven calendar cycles to mature before it becomes dusty, musty, and white-flowered—seven years to muster just one blossom; meanwhile, the chamise I drive past is on full display.

The fact of the New Wash has me curious if there’s an Old Wash. I also wonder what constitutes a gulch versus a wash, if an arroyo is the same thing. The air conditioner hums as I ponder, providing the minor miracle of cold air as the temperature guage on the dash clicks past ninety. Dressed in a light shirt and rolled up jeans, I even consider being cold. I look down to see my hand is trembling. Goddammit. I turn down the AC, but, as my hand continues its St. Vitus dance, I suspect this will do nothing to stop the mounting shakes. Not the tremors. Please, goddammit, any other day. I’d rather this not be more difficult a drive than it already is. Just get me to Phoenix.

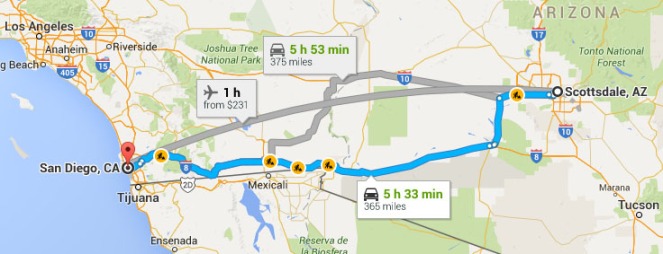

San Diego to Phoenix is actually, should actually, be incredibly easy. By GPS account you take exactly three turns over the span of near-four hundred miles before arriving at Camelback’s base.  Regardless of uncomplication, there’s still the steep and plummeting spiral toward the desert floor, then the white hot spaces with white skies in between: perils of the 8. There are also the stretches of bleached asphalt–too long–before any welcome distance markers. It makes me nervous to say the least. Too many miles of road separate nothing from nothing. Might seem romantic to some, these wide open spaces, but I’m not enamored with anything less than a green freeway sign remarking, ‘You are here.’

Regardless of uncomplication, there’s still the steep and plummeting spiral toward the desert floor, then the white hot spaces with white skies in between: perils of the 8. There are also the stretches of bleached asphalt–too long–before any welcome distance markers. It makes me nervous to say the least. Too many miles of road separate nothing from nothing. Might seem romantic to some, these wide open spaces, but I’m not enamored with anything less than a green freeway sign remarking, ‘You are here.’

I hate the Imperial Valley despite the occasional ibis that happens in the occasional field, or the spectacularly white dunes that occur briefly on the way to Yuma. A trailer park outside El Centro proclaims ‘Shangri-La!’ and, glitching, I all too handily call its bluff.

***

Italo had the clever idea of soldering chain-link into a frozen-upright position, so that it never collapses into coils on the floor. Cunning immortality, if you think about it.

Italo had the clever idea of soldering chain-link into a frozen-upright position, so that it never collapses into coils on the floor. Cunning immortality, if you think about it. done up in color thousands of years ago. All this garish egg paint. It’s only white now,” he said dangling a demitasse from his left pinky.

done up in color thousands of years ago. All this garish egg paint. It’s only white now,” he said dangling a demitasse from his left pinky.

beveled constructions, romantic in their concrete and wire defiance of physics. The city was a leaden gray exercise in suspension.

beveled constructions, romantic in their concrete and wire defiance of physics. The city was a leaden gray exercise in suspension. Chris half-heaves himself over the railing, anchored by his elbows. He lands back on the concrete in soft sneakers.

Chris half-heaves himself over the railing, anchored by his elbows. He lands back on the concrete in soft sneakers.